Posts

| « | February 2026 | » | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

by Michael Urman

Cairo is a powerful 2d graphics library. This document introduces you to how cairo works and many of the functions you will use to create the graphic experience you desire.

In order to follow along on your computer, you need the following things:

Alternately, if you're up for a challenge, you can translate the examples to your preferred language and host environment and only need cairo from above. Nis Martensen has graciously done so for the C language; the C translation has been adopted by the cairo project as its tutorial.

Note: All the example code has a dependency on cairo 1.2.0 or higher for cairo.SVGSurface. In addition several examples need push_group() and pop_group(), and the radial gradients require 1.4 for proper rendering. In a pinch you can work around the first by changing instances of cairo.SVGSurface(filename + '.svg', width, height) to cairo.ImageSurface(cairo.FORMAT_ARGB32, width, height), but really you should consider upgrading.

Translations: fr.

In order to explain the operations used by cairo, we first delve into a model of how cairo models drawing. There are only a few concepts involved, which are then applied over and over by the different methods. First I'll describe the nouns: destination, source, mask, path, and context. After that I'll describe the verbs which offer ways to manipulate the nouns and draw the graphics you wish to create. And don't read this now, but here's the code behind all the diagrams.

If you find the descriptions below to be too sparse, Donn Ingle has created at-a-glance overview diagrams in SVG which try to tie everything together. They require Inkscape (or similar) to view, as well as two specific fonts for correct appearance. Zoom in on each "page" as you follow along. Donn requests that you download and share the diagrams on your own website if you find them useful.

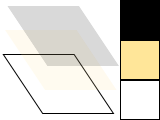

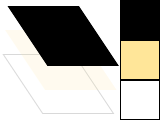

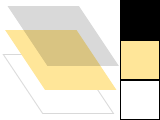

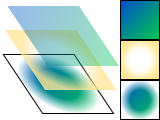

Cairo's nouns are somewhat abstract. To make them concrete I'm including diagrams that depict how they interact. The first three nouns are the three layers in the diagrams you see in this section. The fourth noun, the path, is drawn on the middle layer when it is relevant. The final noun, the context, isn't shown.

The destination is the surface on which you're drawing. It may be tied to an array of pixels like in these PyGTK tutorials, or it might be tied to a SVG or PDF file, or something else. This surface collects the elements of your graphic as you apply them, allowing you to build up a complex work as though painting on a canvas.

The destination is the surface on which you're drawing. It may be tied to an array of pixels like in these PyGTK tutorials, or it might be tied to a SVG or PDF file, or something else. This surface collects the elements of your graphic as you apply them, allowing you to build up a complex work as though painting on a canvas.

The source is the "paint" you're about to work with. I show this as it is—plain black for several examples—but translucent to show lower layers. Unlike real paint, it doesn't have to be a single color; it can be a pattern or even a previously created destination surface. Also unlike real paint it can contain transparency information—the Alpha channel.

The source is the "paint" you're about to work with. I show this as it is—plain black for several examples—but translucent to show lower layers. Unlike real paint, it doesn't have to be a single color; it can be a pattern or even a previously created destination surface. Also unlike real paint it can contain transparency information—the Alpha channel.

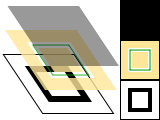

The mask is the most important piece: it controls where you apply the source to the destination. I will show it as a yellow layer with holes where it lets the source through. When you apply a drawing verb, it's like you stamp the source to the destination. Anywhere the mask allows, the source is copied. Anywhere the mask disallows, nothing happens.

The mask is the most important piece: it controls where you apply the source to the destination. I will show it as a yellow layer with holes where it lets the source through. When you apply a drawing verb, it's like you stamp the source to the destination. Anywhere the mask allows, the source is copied. Anywhere the mask disallows, nothing happens.

The path is somewhere between part of the mask and part of the context. I will show it as thin green lines on the mask layer. It is manipulated by path verbs, then used by drawing verbs.

The context keeps track of everything that verbs affect. It tracks one source, one destination, and one mask. It also tracks several helper variables like your line width and style, your font face and size, and more. Most importantly it tracks the path, which is turned into a mask by drawing verbs.

The reason you are using cairo in a program is to draw. Cairo internally draws with one fundamental drawing operation: the source and mask are freely placed somewhere over the destination. Then the layers are all pressed together and the paint from the source is transferred to the destination wherever the mask allows it. To that extent the following five drawing verbs, or operations, are all similar. They differ by how they construct the mask.

The stroke() operation takes a virtual pen along the path. It allows the source to transfer through the mask in a thin (or thick) line around the path, according to the pen's line width, dash style, and line caps.

The stroke() operation takes a virtual pen along the path. It allows the source to transfer through the mask in a thin (or thick) line around the path, according to the pen's line width, dash style, and line caps.

Cairo Tutorial: Diagrams (Section #stroke)

cr.set_line_width(0.1)

cr.set_source_rgb(0, 0, 0)

cr.rectangle(0.25, 0.25, 0.5, 0.5)

cr.stroke()

The fill() operation instead uses the path like the lines of a coloring book, and allows the source through the mask within the hole whose boundaries are the path. For complex paths (paths with multiple closed sub-paths—like a donut—or paths that self-intersect) this is influenced by the fill rule. Note that while stroking the path transfers the source for half of the line width on each side of the path, filling a path fills directly up to the edge of the path and no further.

The fill() operation instead uses the path like the lines of a coloring book, and allows the source through the mask within the hole whose boundaries are the path. For complex paths (paths with multiple closed sub-paths—like a donut—or paths that self-intersect) this is influenced by the fill rule. Note that while stroking the path transfers the source for half of the line width on each side of the path, filling a path fills directly up to the edge of the path and no further.

Cairo Tutorial: Diagrams (Section #fill)

cr.set_source_rgb(0, 0, 0)

cr.rectangle(0.25, 0.25, 0.5, 0.5)

cr.fill()

The show_text() operation forms the mask from text. It may be easier to think of show_text() as a shortcut for creating a path with text_path() and then using fill() to transfer it. Be aware show_text() caches glyphs so is much more efficient if you work with a lot of text.

The show_text() operation forms the mask from text. It may be easier to think of show_text() as a shortcut for creating a path with text_path() and then using fill() to transfer it. Be aware show_text() caches glyphs so is much more efficient if you work with a lot of text.

Cairo Tutorial: Diagrams (Section #text)

cr.set_source_rgb(0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

cr.select_font_face("Georgia",

cairo.FONT_SLANT_NORMAL, cairo.FONT_WEIGHT_BOLD)

cr.set_font_size(1.2)

x_bearing, y_bearing, width, height = cr.text_extents("a")[:4]

cr.move_to(0.5 - width / 2 - x_bearing, 0.5 - height / 2 - y_bearing)

cr.show_text("a")

The paint() operation uses a mask that transfers the entire source to the destination. Some people consider this an infinitely large mask, and others consider it no mask; the result is the same. The related operation paint_with_alpha() similarly allows transfer of the full source to destination, but it transfers only the provided percentage of the color.

The paint() operation uses a mask that transfers the entire source to the destination. Some people consider this an infinitely large mask, and others consider it no mask; the result is the same. The related operation paint_with_alpha() similarly allows transfer of the full source to destination, but it transfers only the provided percentage of the color.

Cairo Tutorial: Diagrams (Section #paint)

cr.set_source_rgb(0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

cr.paint_with_alpha(0.5)

The mask() and mask_surface() operations allow transfer according to the transparency/opacity of a second source pattern or surface. Where the pattern or surface is opaque, the current source is transferred to the destination. Where the pattern or surface is transparent, nothing is transferred.

The mask() and mask_surface() operations allow transfer according to the transparency/opacity of a second source pattern or surface. Where the pattern or surface is opaque, the current source is transferred to the destination. Where the pattern or surface is transparent, nothing is transferred.

Cairo Tutorial: Diagrams (Section #mask)

self.linear = cairo.LinearGradient(0, 0, 1, 1)

self.linear.add_color_stop_rgb(0, 0, 0.3, 0.8)

self.linear.add_color_stop_rgb(1, 0, 0.8, 0.3)

self.radial = cairo.RadialGradient(0.5, 0.5, 0.25, 0.5, 0.5, 0.75)

self.radial.add_color_stop_rgba(0, 0, 0, 0, 1)

self.radial.add_color_stop_rgba(0.5, 0, 0, 0, 0)

cr.set_source(self.linear)

cr.mask(self.radial)

In order to create an image you desire, you have to prepare the context for each of the drawing verbs. To use stroke() or fill() you first need a path. To use show_text() you must position your text by its insertion point. To use mask() you need a second source pattern or surface. And to use any of the operations, including paint(), you need a primary source.

There are three main kinds of sources in cairo: colors, gradients, and images. Colors are the simplest; they use a uniform hue and opacity for the entire source. You can select these without any preparation with set_source_rgb() and set_source_rgba(). Using set_source_rgb(r, g, b) is equivalent to using set_source_rgba(r, g, b, 1.0), and it sets your source color to use full opacity.

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #rgba)

cr.set_source_rgb(0, 0, 0)

cr.move_to(0, 0)

cr.line_to(1, 1)

cr.move_to(1, 0)

cr.line_to(0, 1)

cr.set_line_width(0.2)

cr.stroke()

cr.rectangle(0, 0, 0.5, 0.5)

cr.set_source_rgba(1, 0, 0, 0.80)

cr.fill()

cr.rectangle(0, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5)

cr.set_source_rgba(0, 1, 0, 0.60)

cr.fill()

cr.rectangle(0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5)

cr.set_source_rgba(0, 0, 1, 0.40)

cr.fill()

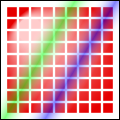

Gradients describe a progression of colors by setting a start and stop reference location and a series of "stops" along the way. Linear gradients are built from two points which pass through parallel lines to define the start and stop locations. Radial gradients are also built from two points, but each has an associated radius of the circle on which to define the start and stop locations. Stops are added to the gradient with add_color_stop_rgb() and add_color_stop_rgba() which take a color like set_source_rgb*(), as well as an offset to indicate where it lies between the reference locations. The colors between adjacent stops are averaged over space to form a smooth blend. Finally, the behavior beyond the reference locations can be controlled with set_extend(). (TODO)

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #gradient)

radial = cairo.RadialGradient(0.25, 0.25, 0.1, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5)

radial.add_color_stop_rgb(0, 1.0, 0.8, 0.8)

radial.add_color_stop_rgb(1, 0.9, 0.0, 0.0)

for i in range(1, 10):

for j in range(1, 10):

cr.rectangle(i/10.0 - 0.04, j/10.0 - 0.04, 0.08, 0.08)

cr.set_source(radial)

cr.fill()

linear = cairo.LinearGradient(0.25, 0.35, 0.75, 0.65)

linear.add_color_stop_rgba(0.00, 1, 1, 1, 0)

linear.add_color_stop_rgba(0.25, 0, 1, 0, 0.5)

linear.add_color_stop_rgba(0.50, 1, 1, 1, 0)

linear.add_color_stop_rgba(0.75, 0, 0, 1, 0.5)

linear.add_color_stop_rgba(1.00, 1, 1, 1, 0)

cr.rectangle(0.0, 0.0, 1, 1)

cr.set_source(linear)

cr.fill()

Images include both surfaces loaded from existing files with cairo.ImageSurface.create_from_png() and surfaces created from within cairo as an earlier destination. As of cairo 1.2, the easiest way to make and use an earlier destination as a source is with push_group() and either pop_group() or pop_group_to_source(). Use pop_group_to_source() to use it just until you select a new source, and pop_group() when you want to save it so you can select it over and over again with set_source().

Cairo always has an active path. If you call stroke() it will draw the path with your line settings. If you call fill() it will fill the inside of the path. But as often as not, the path is empty, and both calls will result in no change to your destination. Why is it empty so often? For one, it starts that way; but more importantly after each stroke() or fill() it is emptied again to let you start building your next path.

What if you want to do multiple things with the same path? For instance to draw a red rectangle with a black border, you would want to fill the rectangle path with a red source, then stroke the same path with a black source. A rectangle path is easy to create multiple times, but a lot of paths are more complex.

Cairo supports easily reusing paths by having alternate versions of its operations. Both draw the same thing, but the alternate doesn't reset the path. For stroking, alongside stroke() there is stroke_preserve(); for filling, fill_preserve() joins fill(). Even setting the clip has a preserve variant. Apart from choosing when to preserve your path, there are only a couple common operations.

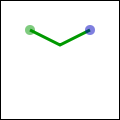

Cairo uses a connect-the-dots style system when creating paths. Start at 1, draw a line to 2, then 3, and so forth. When you start a path, or when you need to start a new sub-path, you want it to be like point 1: it has nothing connecting to it. For this, use move_to(). This sets the current reference point without making the path connect the previous point to it. There is also a relative coordinate variant, rel_move_to(), which sets the new reference a specified distance away from the current reference instead. After setting your first reference point, use the other path operations which both update the reference point and connect to it in some way.

Cairo uses a connect-the-dots style system when creating paths. Start at 1, draw a line to 2, then 3, and so forth. When you start a path, or when you need to start a new sub-path, you want it to be like point 1: it has nothing connecting to it. For this, use move_to(). This sets the current reference point without making the path connect the previous point to it. There is also a relative coordinate variant, rel_move_to(), which sets the new reference a specified distance away from the current reference instead. After setting your first reference point, use the other path operations which both update the reference point and connect to it in some way.

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #moveto)

cr.move_to(0.25, 0.25)

Whether with absolute coordinates line_to() (extend the path from the reference to this point), or relative coordinates rel_line_to() (extend the path from the reference this far in this direction), the path connection will be a straight line. The new reference point will be at the other end of the line.

Whether with absolute coordinates line_to() (extend the path from the reference to this point), or relative coordinates rel_line_to() (extend the path from the reference this far in this direction), the path connection will be a straight line. The new reference point will be at the other end of the line.

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #lineto)

cr.line_to(0.5, 0.375)

cr.rel_line_to(0.25, -0.125)

Arcs are parts of the outside of a circle. Unlike straight lines, the point you directly specify is not on the path. Instead it is the center of the circle that makes up the addition to the path. Both a starting and ending point on the circle must be specified, and these points are connected either clockwise by arc() or counter-clockwise by arc_negative(). If the previous reference point is not on this new curve, a straight line is added from it to where the arc begins. The reference point is then updated to where the arc ends. There are only absolute versions.

Arcs are parts of the outside of a circle. Unlike straight lines, the point you directly specify is not on the path. Instead it is the center of the circle that makes up the addition to the path. Both a starting and ending point on the circle must be specified, and these points are connected either clockwise by arc() or counter-clockwise by arc_negative(). If the previous reference point is not on this new curve, a straight line is added from it to where the arc begins. The reference point is then updated to where the arc ends. There are only absolute versions.

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #arc)

cr.arc(0.5, 0.5, 0.25 * sqrt(2), -0.25 * pi, 0.25 * pi)

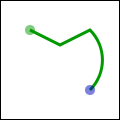

Curves in cairo are cubic Bézier splines. They start at the current reference point and smoothly follow the direction of two other points (without going through them) to get to a third specified point. Like lines, there are both absolute (curve_to()) and relative (rel_curve_to()) versions. Note that the relative variant specifies all points relative to the previous reference point, rather than each relative to the preceding control point of the curve.

Curves in cairo are cubic Bézier splines. They start at the current reference point and smoothly follow the direction of two other points (without going through them) to get to a third specified point. Like lines, there are both absolute (curve_to()) and relative (rel_curve_to()) versions. Note that the relative variant specifies all points relative to the previous reference point, rather than each relative to the preceding control point of the curve.

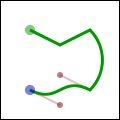

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #curveto)

cr.rel_curve_to(-0.25, -0.125, -0.25, 0.125, -0.5, 0)

Cairo can also close the path by drawing a straight line to the beginning of the current sub-path. This straight line can be useful for the last edge of a polygon, but is not directly useful for curve-based shapes. A closed path is fundamentally different from an open path: it's one continuous path and has no start or end. A closed path has no line caps for there is no place to put them.

Cairo can also close the path by drawing a straight line to the beginning of the current sub-path. This straight line can be useful for the last edge of a polygon, but is not directly useful for curve-based shapes. A closed path is fundamentally different from an open path: it's one continuous path and has no start or end. A closed path has no line caps for there is no place to put them.

Cairo Tutorial: Drawing (Section #closepath)

cr.close_path()

Finally text can be turned into a path with text_path(). Paths created from text are like any other path, supporting stroke or fill operations. This path is placed anchored to the current reference point, so move_to() your desired location before turning text into a path. However there are performance concerns to doing this if you are working with a lot of text; when possible you should prefer using the verb show_text() over text_path() and fill().

To use text effectively you need to know where it will go. The methods font_extents() and text_extents() get you this information. Since this diagram is hard to see so small, I suggest getting its source and bumping the size up to 600. It shows the relation between the reference point (red dot); suggested next reference point (blue dot); bounding box (dashed blue lines); bearing displacement (solid blue line); and height, ascent, baseline, and descent lines (dashed green).

To use text effectively you need to know where it will go. The methods font_extents() and text_extents() get you this information. Since this diagram is hard to see so small, I suggest getting its source and bumping the size up to 600. It shows the relation between the reference point (red dot); suggested next reference point (blue dot); bounding box (dashed blue lines); bearing displacement (solid blue line); and height, ascent, baseline, and descent lines (dashed green).

The reference point is always on the baseline. The descent line is below that, and reflects a rough bounding box for all characters in the font. However it is an artistic choice intended to indicate alignment rather than a true bounding box. The same is true for the ascent line above. Next above that is the height line, the artist-recommended spacing between subsequent baselines. All three of these are reported as distances from the baseline, and expected to be positive despite their differing directions.

The bearing is the displacement from the reference point to the upper-left corner of the bounding box. It is often zero or a small positive value for x displacement, but can be negative x for characters like j as shown; it's almost always a negative value for y displacement. The width and height then describe the size of the bounding box. The advance takes you to the suggested reference point for the next letter. Note that bounding boxes for subsequent blocks of text can overlap if the bearing is negative, or the advance is smaller than the width would suggest.

In addition to placement, you also need to specify a face, style, and size. Set the face and style together with select_font_face(), and the size with set_font_size(). If you need even finer control, try getting a cairo.FontOptions() with get_font_options(), tweaking it, and setting it with set_font_options().

When working in GTK+, there is also the pangocairo.CairoContext. I think using cairo's builtin font functionality is more suitable for handling text with picky size restrictions and complex positioning, whereas pangocairo.CairoContext may be more suitable when you're trying to create widget text that looks like other GTK+ widget text, or has complex font needs or a wrapping layout.

Transforms have three major uses. First they allow you to set up a coordinate system that's easy to think in and work in, yet have the output be of any size. Second they allow you to make helper functions that work at or around a (0, 0) but can be applied anywhere in the output image. Thirdly they let you deform the image, turning a circular arc into an elliptical arc, etc. Transforms are a way of setting up a relation between two coordinate systems. The device-space coordinate system is tied to the surface, and cannot change. The user-space coordinate system matches that space by default, but can be changed for the above reasons. The helper functions user_to_device() and user_to_device_distance() tell you what the device-coordinates are for a user-coordinates position or distance. Correspondingly device_to_user() and device_to_user_distance() tell you user-coordinates for a device-coordinates position or distance. Remember to send positions through the non-distance variant, and relative moves or other distances through the distance variant.

I leverage all of these reasons to draw the diagrams in this document. Whether I'm drawing 120 x 120 or 600 x 600, I use scale() to give me a 1.0 x 1.0 workspace. To place the results along the right column, such as in the discussion of cairo's drawing model, I use translate(). And to add the perspective view for the overlapping layers, I set up an arbitrary deformation with transform() on a cairo.Matrix().

To understand your transforms, read them bottom to top, applying them to the point you're drawing. To figure out which transforms to create, think through this process in reverse. For example if I want my 1.0 x 1.0 workspace to be 100 x 100 pixels in the middle of a 120 x 120 pixel surface, I can set it up one of three ways:

Use the first when relevant because it is often the most readable; use the third when necessary to access additional control not available with the primary functions.

Be careful when trying to draw lines while under transform. Even if you set your line width while the scale factor was 1, the line width setting is always in user-coordinates and isn't modified by setting the scale. While you're operating under a scale, the width of your line is multiplied by that scale. To specify a width of a line in pixels, use device_to_user_distance() to turn a (1, 1) device-space distance into, for example, a (0.01, 0.01) user-space distance. Note that if your transform deforms the image there isn't necessarily a way to specify a line with a uniform width.

This wraps up the tutorial. It doesn't cover all functions in cairo, so for some advanced

lesser-used features, you'll need to look elsewhere. The code behind the examples uses a handful of techniques that aren't described within, so analyzing them may be a good first step. Other examples on cairographics.org lead in different directions. As with everything, there's a large gap between knowing the rules of the tool, and being able to use it well. The final section of this document provides some ideas to help you traverse parts of the gap.

In the previous sections you should have built up a firm grasp of the operations cairo uses to create images. In this section I've put together a small handful of snippets I've found particularly useful or non-obvious. I'm still new to cairo myself, so there may be other better ways to do these things. If you find a better way, or find a cool way to do something else, let me know and perhaps I can incorporate it into these tips.

When you're working under a uniform scaling transform, you can't just use pixels for the width of your line. However it's easy to translate it with the following shortcut:

cr.set_line_width(max(cr.device_to_user_distance(pixel_width, pixel_width)))

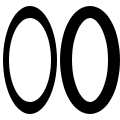

When you're working under a deforming scale, you may wish to still have line widths that are uniform in device space. For this you should return to a uniform scale before you stroke the path. In the image, the arc on the left is stroked under a deformation, while the arc on the right is stroked under a uniform scale.

Cairo Tutorial: Tips and Tricks (Section #deform)

cr.save()

cr.scale(0.5, 1)

cr.arc(0.5, 0.5, 0.40, 0, 2 * pi)

cr.stroke()

cr.translate(1, 0)

cr.arc(0.5, 0.5, 0.40, 0, 2 * pi)

cr.restore()

cr.stroke()

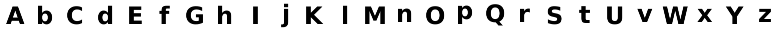

When you try to center text letter by letter at various locations, you have to decide how you want to center it. For example the following code will actually center letters individually, leading to poor results when your letters are of different sizes. (Unlike most examples, here I assume a 26 x 1 workspace.)

Cairo Tutorial: Tips and Tricks (Section #center)

for cx, letter in enumerate('AbCdEfGhIjKlMnOpQrStUvWxYz'):

xbearing, ybearing, width, height, xadvance, yadvance = (

cr.text_extents(letter))

cr.move_to(cx + 0.5 - xbearing - width / 2,

0.5 - ybearing - height / 2)

cr.show_text(letter)

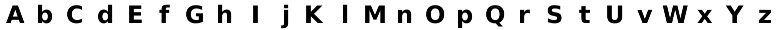

Instead the vertical centering must be based on the general size of the font, thus keeping your baseline steady. Note that the exact positioning now depends on the metrics provided by the font itself, so the results are not necessarily the same from font to font.

Cairo Tutorial: Tips and Tricks (Section #baseline)

fascent, fdescent, fheight, fxadvance, fyadvance = cr.font_extents()

for cx, letter in enumerate('AbCdEfGhIjKlMnOpQrStUvWxYz'):

xbearing, ybearing, width, height, xadvance, yadvance = (

cr.text_extents(letter))

cr.move_to(cx + 0.5 - xbearing - width / 2,

0.5 - fdescent + fheight / 2)

cr.show_text(letter)

(NOTE)